This article will introduce the need for implementing iterators in writing a maintainable and flexible data structure.

Before we start the series and actually implement data structures, it is important to motivate our high-level design goals. That said, we want to be able to interface our data structure consistently. The benefit we gain from this is to be able to abstract shared interfaces among categories of data structures. Consequently, algorithms that wish to operate on our data structures may do so with the help of this shared common interface known as Iterators.

Why iterators are important?

An iterator is a particular design pattern that allows one to traverse (or iterate) over a data structure. This pattern decouples algorithms and data structures that mediate their interaction. The inspiration for this can be drawn from the architecture of the C++ Standard Template Library that makes great use of iterators in communicating between algorithms and data structures.

Iterator decouples Data Structures and Algorithms.

We achieve flexible software systems because of iterators. Hold on, how many iterators are there?

The motivation behind crafting an iterator depends on how we want to orient the data structure to our algorithm. Our algorithms may operate as if our data structure is ordered backward with a reverse iterator, we may access elements randomly using random iterator, we may access data sequentially using forward iterator and the list does not end there.

Since we concern ourselves in C++, we make use of pointer semantics for consistently interfacing the data structure as if they were a pointer. Consequently, one may assert that iterators are generalizations of pointers but they have subtle differences in regards to the intent of use. Because iterators are expected to behave like pointers, their interface may guide the semantics of any kind of data structure. In contrast, traversing in a data structure with raw pointers hide the intent of use and often introduce an unnecessary amount of complexity.

Let us consider two cases: first with linear data structures and second with non-linear data structures. For the first case, let us take quick a look at an Array. Think about how we might communicate in an array with pointers and iterators.

std::array<int,3> array {1,2,3,4,5};

std::array<int,3>::pointer array_ptr = array.data();

for(size_t i = 0; i < array.size(); ++i)

std::cout << array_ptr[i] << '\n';

The above snippet of code demonstrates how we may traverse through an array using a pointer. For a linear data structure, this is trivial. Now consider how this may be written with iterators. There are two ways of doing this, the first part is more explicit while the second part is terser.

std::array<int,3> array {1,2,3,4,5};

for(std::array<int,3>::iterator it = array.begin(); it != array.end(); ++it)

std::cout << *it << '\n';

std::array<int,3> array {1,2,3,4,5};

for(int&i: array)

std::cout << i << '\n';

Since all programs result in the same output, it seems that iterators are just a fancy thing that exactly does what we expect a pointer would have. Why do we bother writing iterators if a pointer can suffice its functionality? This question leads us to our second case: traversals in a non-linear data structure.

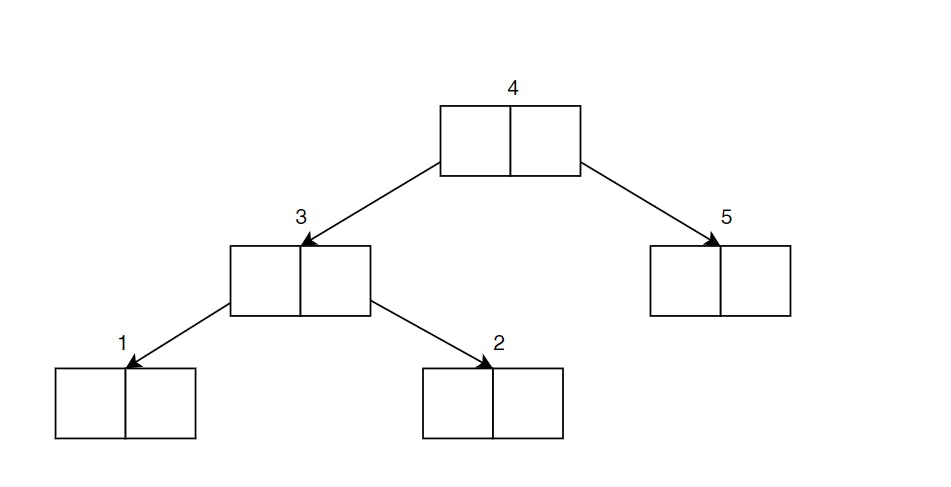

The above figure is a Binary Search Tree (BST). Since we have not formally introduced this yet, we will take a sneak peek at traversing BST. There are three ways we can do this, and each has a different form of ordering. But let us consider the simplest: in order traversal where we start from the left-most branch resulting to 1,2,3,4,5. Now, imagine using a pointer to walk in our tree.

void inorder(Node *node) {

if (node != nullptr) {

traverse_inorder(node->left);

std::cout << node->data << " ";

traverse_inorder(node->right);

}

}

The above snippet is a piece of code that is very specific concerning the data structure. It assumes that you have an access to a Node which represents a wrapper on the data. In most cases, we cannot afford this. We want our algorithms to communicate with our data structure seamlessly, and we do this by not imposing the user to know the specifics of our data structure, in this case, BST. Consequently, through iterators, algorithms do not need to know about what data structures they will be performing operations on.

BST<int> bst {1,2,3,4,5};

for(int& i: bst)

std::cout << i << '\n';

Suffice to say that iterators behave like pointers in the manner on how they access and traverse a given data structure. But on some occasions, iterators work favorably in accessing more complicated data structures as it separates the internal mechanism and interface which makes using them more intuitive.

Through iterators, algorithms do not need to know about what data structures they will be performing operations on.

In STL, iterators can be accessed using the <iterator> header file (a summary is provided here), but to learn and appreciate iterators, we should know how to write and implement one. Besides, std::iterator has been deprecated since C++17.

Why do we consider writing iterators?

Writing an iterator is a separate skill from writing data structures. The reason why I want to include iterators in our data structure design requirement is twofold:

- Iterators abstract the interface which therefore makes our data structure more flexible in welcoming algorithms as we can define the internal mechanisms on how traversals are supposed to work.

- Iterator is a fundamental aspect of software design; it is a good practice to know about it.

What we will mostly cover are basic iterators for reading and accessing data.

Summary

Iterators serve to be the shared common interface between data structures. Iterators make our request on data structures more consistent which results in making it more flexible. Consequently, algorithms can communicate without knowing the specific implementation of a data structure because of iterators.

References

- Gamma, E., Helm, R., Johnson, R., & Vlissides, J. (1994). Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software.

- cplusplus.com (2021). iterator. cplusplus.com/reference/iterator.

- cppreference.com (2021). std::reverse_iterator. en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/iterator/reverse_...

- Boccara, J. (2018). std::iterator is deprecated: Why, What It Was, and What to Use Instead. Fluent {C++}. fluentcpp.com/2018/05/08/std-iterator-depre...

Photo by Alex Andrews from Pexels

If you enjoyed this content, follow me on my LinkedIn, or subscribe to my newsletter.