Making Sense of Algorithms: General Perspective

features, groups, and modes of searching and evaluating algorithms — forests to the trees.

Algorithms can be a very difficult subject to understand. They come in varying logic expressed in varying languages, implemented in different syntax for varying purposes. Indeed, there are algorithms that are said to be different but works pretty much the same: the distinction can be drawn upon many parameters, one that is common is the nature of how the logic is implemented and how efficient it is based on some constraints usually determined by time and memory it needs — more generally with respect to finite resources. In this article, we shall take a general perspective and build our understanding of algorithms. We shall learn the features and characteristics of an algorithm, a criterion to a group and organize the family of algorithms, and the manner as to how can we decide to use an algorithm as a response to a given problem.

An algorithm describes the ordering of procedures for obtaining specified results.

In the parlance of mathematics and computer science, an algorithm pertains to a finite sequence of well-defined computer-implementable instructions, typically to solve a class of problems or to perform a computation [1–2]. Algorithms are essential for data and information processing in computers. Historically, computers are people that can carry out the process of computations through a series of operations. Thus, the antiquity of algorithms can be traced back to the Babylonian Mathematics of c. 2500 B.C [2] — the division algorithm. Greek mathematicians have used the concept of an algorithm in investigating patterns of numbers such as the Euclidean algorithm which is a method for finding the greatest common divisor given two numbers. And Eratosthenes’ method for finding prime numbers [2].

Broadly speaking, an algorithm is a series of instructions expressed for an agent being capable of carrying through such a process to execute. Further formalizations suggest that an algorithm be expressed by a Turing-complete system [3–4]. A formal system, say a programming language, is said to be Turing-complete if it can emulate the abstract Turing machines. In other words, a Turing-complete language is theoretically capable of expressing all tasks accomplished by computers [5] as Turing machines bear to be the theoretical representation of a computer. Therefore, expressing algorithms in such a manner not only simplifies but also logically formalizes the series of procedures.

On Expressing Algorithms

One can express algorithms in various forms: either in a natural language that we use every day or in an artificial language that is constructed with specified grammatical syntax and vocabularies — e.g. cookbook recipes and methods explained in Pseudocodes. By the same token, algorithms are independent of the languages they are expressed upon. Additionally, there are means as to how we could sort out the representation of algorithms for varying purposes.

In developing a solution for a given problem, one has to follow an iterative development approach — planning, building, testing, and revising. In that sense, a representation of an algorithm, in varying degrees of abstraction, might be helpful for generating solutions. We can categorize these degrees as follows:

- High-level description: a statement that describes an algorithm without necessarily specifying implementation details.

- Implementation description: directives that specify the implementation, plausibly with respect to the language e.g. pseudocodes or C++ code.

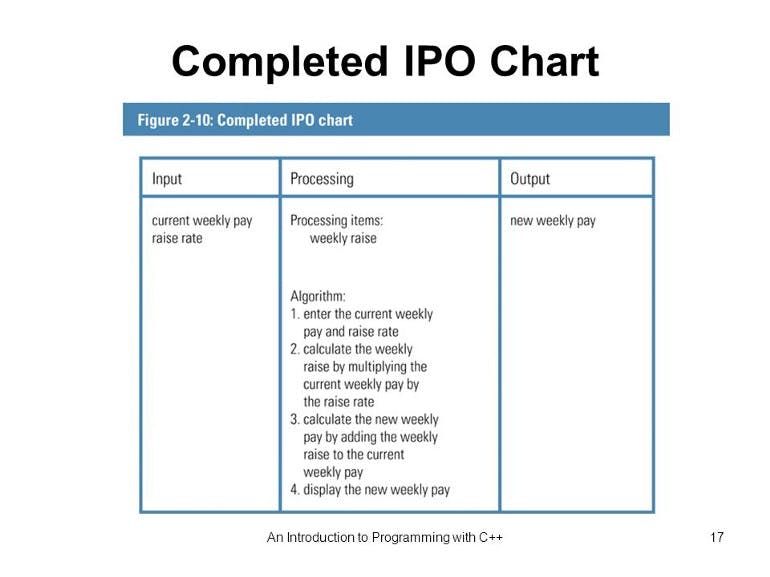

In the same way, data structures and algorithms are represented abstractly (which only gets into the essence of the matter) before it can be implemented in a codebase[4]. One has to begin with a high-level (abstract) description to picture the given case: for this inputs what are the expected outputs? What are the key procedures? Among others, Input-Processing-Output (IPO) diagrams might be helpful for this.

In expressing algorithms, one has to keep in mind that it needs to be concise because vague expressions lead to confusion which could impact the time it takes to implement the algorithm. In that sense, natural language should not be left without constraints; constrained natural language is in fact an artificial language[6]. We will not be going to talk about the linguistic features of these expressions further since the notion of an algorithm does not depend on the language: for practical reasons, we ought to specify and constrain linguistic features to account for simplicity, organization, and clarity when we express algorithms. The point is that expressing algorithms has to be concise (in a manner that is descriptive and imperative).

It might be helpful if you learn to use visual languages (such as UML and flowcharts) and pseudocodes to develop the design of your algorithm.

Features of an Algorithm [4]

As the situation varies, we are presented with different frames of problems; we are also tasked to formulate different flavors of our recipe — algorithms.

It is important to define the features of an algorithm to have some sense of selecting the ideal algorithm. Here we define helpful terms one has to keep in mind before deciding which kind of algorithm to implement in a given situation. As the situation varies, we are presented with different problems, we are also tasked to formulate different flavors of our recipe — algorithms.

- Correctness — pertains to the relevance or the appropriate use-case of an algorithm to solving a problem.

- Maintainability — often pertains to the reliability and the readability of an algorithm.

- Efficiency — pertains to how an algorithm’s performance changes as the size of the problem change.

Characteristics of an Algorithm

While algorithms describe procedures, not all procedures can be called an algorithm. In this sense, an algorithm should have the following characteristics[7]:

- Unambiguous — in expressing an algorithm it should not be vague. Each step should be indicative of the process as precisely as possible.

- Input — an algorithm should have 0 or more well-defined inputs.

- Output — an algorithm should have 1 or more well-defined outputs, and it should match the desired output.

- Finiteness — an algorithm must terminate after a finite number of executions.

- Feasibility — an algorithm should be feasible with the available resources.

- Independent — an algorithm should have step-by-step directions, which should be independent of any programming code.

How do we classify algorithms? And how do we determine which one to use?

Algorithms can be classified with respect to the implementation, design paradigm, field of study, and complexity. It should be noted that the choice of an algorithm depends on the problem and [computational] resources of which we can ground our selection. That is to say, that there will be trade-offs involved in such a process and we should account for efficiency, which we can define as the modality of the quality of performance over resources (such as time), in solving a given problem.

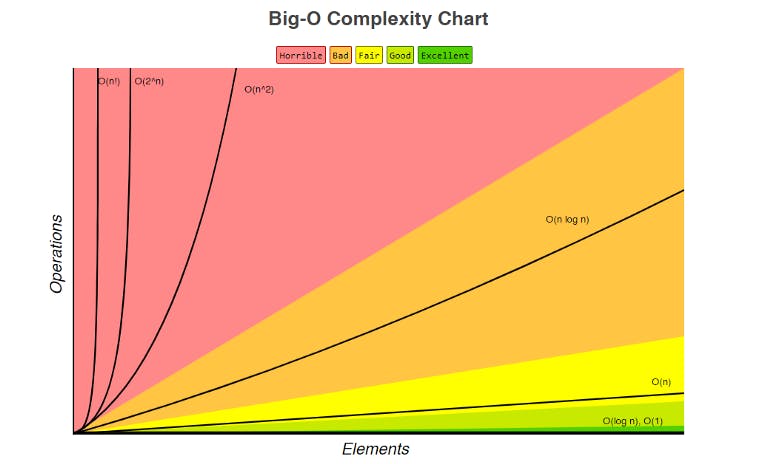

Since performance over time is a significant indicator of which algorithm is appropriate for a given task, the Space and Time complexity of a given algorithm serves as a map of which direction we shall proceed in searching for our algorithm. In doing so, it is important to note that a theoretical construct that classifies an algorithm according to their runtime and space requirement under a worst-case scenario called the Big-O [4,7].

The big-O notation is a member of the asymptotic notation family which classifies an algorithm’s runtime in the worse possible event e.g. in searching for the index of an array the element we are finding is in the last element of an array. That is why the big-O notation is used for classifying an algorithm.

The graph above shows the growth of an algorithm over time given a number of inputs (elements). That said, the algorithms that belong to \(O(log\ n)\) and \(O(1)\) [read as big-O of log n and big-O of 1] are ideal for a given task. However, not all problems are solvable by an algorithm that belongs to \(O(1)\) and \(O(log\ n)\) class. Hence, one shall evaluate the trade-offs.

References:

- Math Vault (n.d.). The Definitive Glossary of Higher Mathematical Jargon. Retrieved at: mathvault.ca/math-glossary/#algo.

- Chabert, Jean-Luc (2012). A History of Algorithms: From the Pebble to the Microchip. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9783642181924.

- Minsky, M. (1967). Computation: Finite and Infinite Machines (First ed.). Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. ISBN 978–0–13–165449–5.

- Stephens, R. (2019). Essential Algorithms: A Practical Approach to Computer Algorithms Using Python and C. John Wiley & Sons.

- Yan, S. Y. (2019). Computational Preliminaries. In Cybercryptography: Applicable Cryptography for Cyberspace Security (pp. 143–172). Springer, Cham.

- Okrent, A.(2013). Artificial Languages. obo in Linguistics. doi: 10.1093/obo/9780199772810–0164.

- Tutorialspoint (n.d.). Data Structures| Algorithms Basics. Retrieved at: tutorialspoint.com/data_structures_algorith...